Pillars

By Anthony Casperson

10-14-23

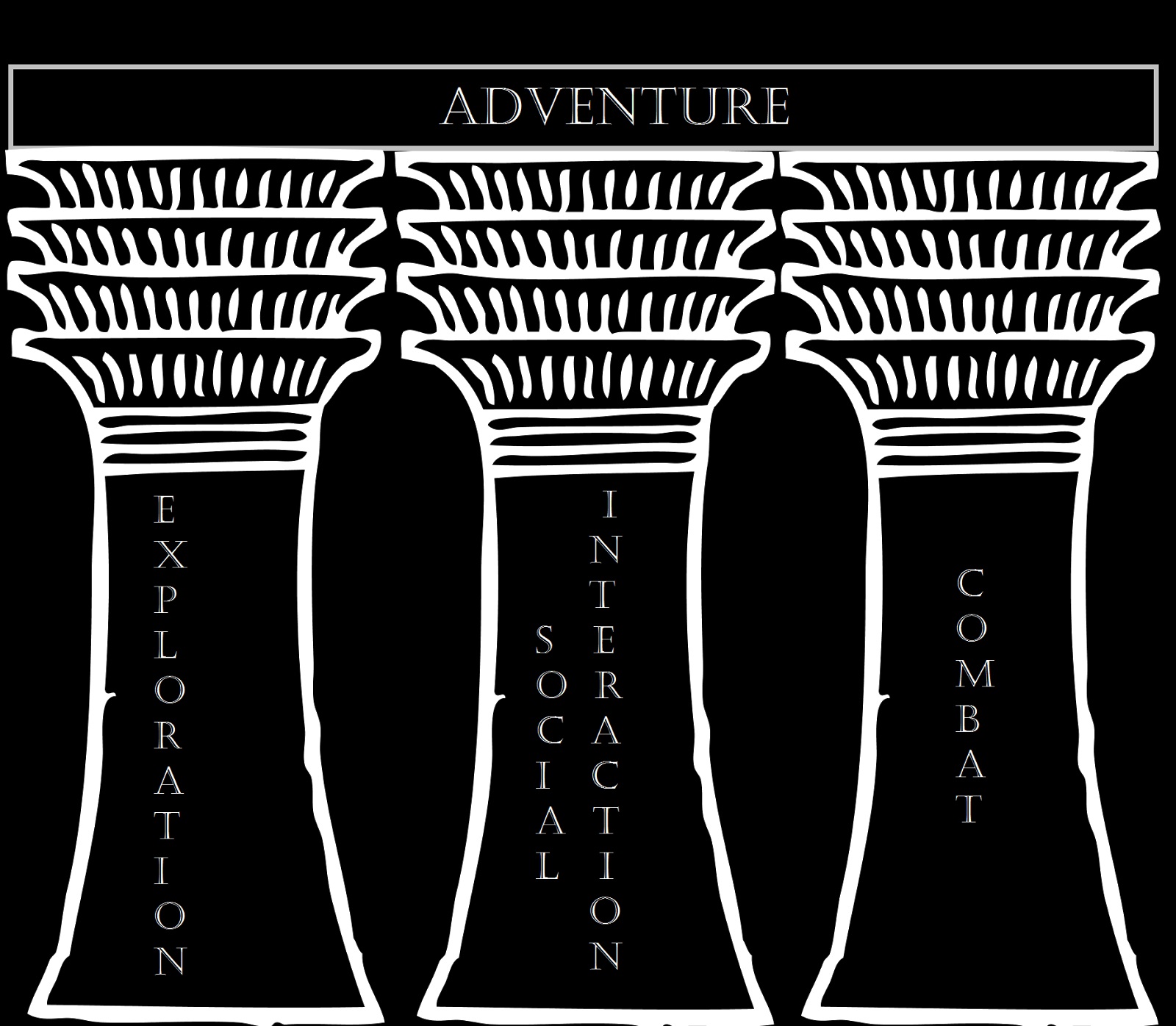

A number of tabletop RPGs take the time in their explanation of the game’s rule set to describe the core modes of play that the characters will experience. Often these descriptors are often termed as “pillars” of the game.

The commonly used triad of pillars are: Exploration, Social Interaction, and Combat. Other terms might be used to describe the same things, or additional pillars can be added, but they tend to account for the same basic idea of modern roleplaying games.

However, one game designer whom I’ve heard speak about this topic has mentioned that what a system calls the fundamental aspect of their game might not actually prove to carry any weight when one plays the game in question. Essentially, these common pillars are given lip service because of historical precedence, but in the practical experience of those involved, something else entirely is shown.

This game designer explains that a game can say that social interaction is a part of it primary drive, but if it doesn’t incentivize the players to engage with social interaction—like rewarding XP for talking the party out of a fight—then how much of a pillar for the game’s experience is it? If the bulk of the rules point toward combat, and XP is only granted because of combat, and 85-90% of the play session’s time is filled with combat, then how can anyone try to proclaim that there’s any pillar other than combat?

Sure, good DMs, GMs, and Lead Storytellers can create environments where these other supposed pillars take greater weight in the gameplay, but this means that they’ve taken a combat-oriented game and added these other aspects to it. The game shouldn’t take credit for that addition.

We can say that something is a pillar to an experience, but if the actions of those involved don’t align with those pillars, then are they really central to the experience in question? Do we not create something entirely different than described if what’s supposedly a pillar becomes undermined in the practice of the experience?

This illustration popped back up in my head while I was listening to a pastor speak about a particular controversy he faced for allowing certain individuals to take on a teaching role in a church-sponsored conference.

(I’m not going to name names, or give many details because I’m more interested in helping us keep the pillars of our faith as core to our practical experience, instead of wading into a theological battleground that has errors on both sides.)

While this pastor defended the church’s part in holding a conference—which had a few presenters who live in what nearly all of the history of Christianity would call blatant sin—he explained that his personal theology aligned with the historical (and biblical) perspective on the topic. He continued that the church’s leadership has always held that position. And he even spoke of the actions involved as sinful while speaking well of those who struggle with the issue, but don’t give in to the sinful actions that it can lead to.

He was listing out the pillars of biblical theology when it comes to the topic.

But then, he turned to emotional reaction concerning the issue. Essentially, “How can anyone who hasn’t struggled with the issue ever truly help those who also deal with it?” To which my question came, “How can someone who lives in blatant and unrepentant sin ever help people do anything other than tear down those pillars that you so eloquently listed as important to the church’s theological stance?”

Is it truly a pillar of your theological stance? Or have you only paid lip service because of historical precedence, while people’s experience proves otherwise?

A few words of warning before we continue on to any sort of application. One, I’m not talking about people who occasionally fall into sin. Or even have some habit that they plead with God to take away, while seeking the holiness of freedom from the struggle. When I say “blatant and unrepentant sin,” I mean people who see a discrepancy between the bible and their experience, and then claim that there’s something wrong with the bible. They keep on doing whatever they feel is right, while proclaiming the word of God has some fault in it because we’ve become more “enlightened,” or something.

We all have a fallen human nature that makes our selfish desires sound so good and pleasing. And I believe that wounded and still-personally-healing healers can be very helpful to people in the same type of situations. (Hello, I’m Anthony. And this website exists in the hope that I can do the very same thing for people who deal with depression, anxiety, and other struggles that lead us into The Depths of Darkness. I’m not perfect. And never claim to be.)

The hope is that as the healer grows, they can pave the way for others who are just a little behind them in the process of freedom, holiness, and Christ-likeness. But those who claim to help others while they refuse to admit that there’s a problem with their own actions—even praising their stance, in some circumstances—are like a person impaled on a spike trying to take a sliver out of another’s finger. (I think Jesus once said something about specks and logs, which might apply here.)

A second word of warning. I’m not asking anyone to take the stance of this pastor’s detractors. The churchly cancel culture is strong here. They’ve called him a heretic and a false teacher without even taking a second to hear him out.

My personal opinion, is that someone close to him should go to him in brotherly love and explain that an explicitly stated pillar can be undermined—even destroyed—when we allow the practical experience of people engaging with us to point them to something different than what we claim to be about. We can say that we’re all about social interaction, but if all of the mechanics point to combat, is there really a social interaction pillar?

It is only when a person is shown the error of their ways, and then refuses it, that we followers of Jesus should remove ourselves from fellowship with our brother or sister in Christ. And then, only in the hope that restoration can happen. Paul writes as much in 1 Corinthians 5 when he tells the local manifestation of the church there remove from their fellowship a man who was known by all to be in a sexual relationship with his father’s wife. The removal of fellowship is made with the mind that his spirit can be restored.

This leads me to the third word of warning. We followers of Jesus shouldn’t think that we have to remove ourselves from the presence of all sinners. I mean, we can’t get away from ourselves. The command to judge the unrepentant man in 1 Corinthians 5 is given because he claimed to be a fellow follower of Jesus while living in blatant sin.

Paul continues in that same chapter to say that if he meant for the church in Corinth to remove themselves from all sinners, then they’d be removed from the world. It’s only because of the man’s claim to be a follower of Jesus that the harshness of the judgement strikes.

If the man never came to follow Jesus, then such behavior would be expected. Sinners gonna sin. But because he claims the name of Jesus, it becomes a problem for him to not represent the holiness of our Savior.

This is the whole problem with the conference presenters that the pastor was defending. They’re living in blatant and unrepentant sin. If we hold to the standard—the pillars—of the bible, we shouldn’t be giving them positions of teaching and leadership. Instead, we should remove our fellowship from them, in the hope that this absence from the family of God might lead them to true repentance. Then, we can embrace them as people growing in holiness. And after this healing process has taken time in them, they can lead and teach people who struggle with the issue.

If these presenters were not followers of Jesus, I would expect them to live in sin—though, I’d still question their place as presenters in the conference. It’s only because of their claim to be Christians that gives us the biblically-provided right to judge their actions. Again, with the hope that restoration might happen.

The pillars of our faith—and the pillars of biblical theology in specific topics—can be undermined when we allow practical experiences to never witness the pillar in action. It’s just lip service then. Merely a memorized history lesson that we roll our eyes at while regurgitating the words. Something we say because we have to, but has no interaction at all with our regular experience with it.

Words that waste space.

This is why it’s important for us to think about how our actions accentuate or undermine the pillars of our faith. We must allow the practical experience to rise up to the heights of the fundamental aspects that we claim to have.

Let me give us one more example. There’s a reason why I’ve hit this point about restoration so much as I’ve written. To many people today, the idea of calling someone out in judgement for their deeds seems to come from a heart of hatred. That’s the view of many Christians today whenever we speak on any topic.

But because I know that Jesus came to save sinners—to restore humanity to our proper place in relationship with him—it means that restoration must be a pillar of our faith in him.

Many among us—and again, I’m not perfect here either—have undermined that pillar of restoration through our actions. We’ve shown that restoration to proper relationship with God is something we talk about, but never experience. If all we do is shout at each other about how wrong others are, and cast dispersions without a desire to bring about restoration, then do we truly hold to the pillars of the faith ourselves?

There’s a lot that we can learn if we just sit down and ask how many of the pillars of our faith we’re merely giving lip service to. How many do we hold merely because of historical precedence? And how many have we actually shown to be practically experienced?

The answer to that might just prove how unstable our stance is because a pillar or two have crumbled and need to be restored.