Still Despite

By Anthony Casperson

12-12-20

We’ve heard the slow methodical melody hundreds of times. Sung by choirs. Played over touching moments in Christmas movies. And who knows how many other objects sound the rhythm this time of year.

Right when the song Silent Night is about to play, a hush falls over the crowd. It starts out small and quiet. And never really gets much louder. Almost a lullaby.

But it doesn’t really feel true for us all that often. Silent and peaceful are some of the last things I think about when contemplating the season. Activity, hubbub, and noise are more the sounds of the season. (Honestly, my heart isn’t two sizes too small.)

So, when I think about Silent Night, I tend to have a bit of a scoff at the idyllic lyrics.

And it’s not just modern Christmases that are less than silent. Think about the night Jesus actually was born. Births tend to have a lot of pain and screaming, if I understand them correctly. And Mary didn’t have access to an epidural.

That’s not to mention being surrounded by some sort of animals because there were too many people in the city to have proper accommodations. And having to place a newborn into their feeding trough.

Nor does it take into account the barging in of the band of strange shepherds, who had to proclaim this tale of a choir of heaven’s army. And then went out into the night waking up the neighborhood to proclaim the amazing news of their Savior. Luke 2 makes it seem like they’d have put carousing drunks to shame with their revelry.

Silence? Really?

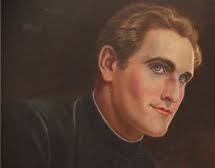

So, I looked up who wrote the lyrics, hoping to discover their purpose in calling it a “silent” night. Joseph Mohr, an Austrian Catholic priest, wrote the words. (Though Franz Xaver Gruber penned the melody to Mohr’s poem.)

It was performed for a midnight mass on Christmas Eve. Initially, I thought about how that makes sense. Even on Christmas Eve, people are going to be sleeping by midnight. Or are, at least, wanting to be. The town would be quiet. And the people would want to be as well.

Maybe, Father Mohr, your situation is silent, or at least close to it. But that’s not common for most people.

Then, I read the rest of the story.

That night in 1818, the church’s organ sat damaged because the river had flooded beforehand. The priest rushed around with the organist (the aforementioned Gruber), trying to figure out what they were going to do for music to celebrate the birth of their Savior.

And that’s when Mohr had an idea.

He’d penned the poem Stille Nacht (German for Silent Night) a couple of years before. And Gruber was gifted in writing music. So the pair hurried to prepare for the quickly approaching service. And the priest would play his guitar as accompaniment, without much practice at all. (This was before electronic amplification, so it would be much quieter than the organ could blast.)

In the middle of disaster, after rushing around to be ready for the moment, the first chord rang out from the stilled heart of the priest.

The silence doesn’t come from our surroundings. There will always be another disaster flowing through. Rather, it is a stillness of the heart despite it all.

Amidst the noise, Mary contemplated all of the events surrounding her. In spite of the damage and poor timing, Joseph Mohr sang the quiet song. And regardless of the disasters around us, our hearts can stand in silent stillness before our Savior who came to die for us.

Jesus, Lord at thy birth.

Joseph Mohr